"The other thing that made things easier," Franklin says, "was that Sandy was not a purely tropical storm." Typical hurricanes are smaller than last week's superstorm, and the models do better with larger systems. When those features tend to be large, then the models do a much better job." For Sandy, the high-pressure block off Greenland, as well as the wintry front blowing in off the land, made life miserable for people in the storm's path but actually helped meteorologists to predict Sandy's track more accurately. It's relatively easy to forecast a hurricane's path, Franklin says, because "all hurricanes get steered by the features that surround them. For 20 five-day forecasts erred by an average of just 100 miles. In the 1990s it was down to about 200 miles. In the 1970s five-day hurricane forecasts were off by 400 miles on average. The NHC's ability to predict the track of a hurricane has been getting dramatically better in recent decades, thanks in part to better satellite data. "So it takes a huge amount of computing to generate a five-to-seven day forecast," Gall says. And at each point the models have to calculate temperature, pressure, and humidity changes at regular intervals-usually every 30 seconds. That's a lot of points (100 trillion, in fact). We're able to do that because we've got more computing power." He explains that a typical model might use a grid that consists of 1 million east–west points by 1 million north–south points by 100 vertical points. "One thing we're doing is running the models at higher resolution. "A lot of things came together this year," Gall says. They take an average of all of the models, which tends to compensate for biases in each individual model, says NHC meteorologist James Franklin. Forecasters at the NHC have a pretty good idea about which models tend to perform better, and they're able to correct for the biases of each based on its past performance. The models digest data differently and may use different equations to simulate how the atmospheric and oceanic conditions will change over time. The NHC bases its forecasts on models from all over the world-including from the Global Forecast System, the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts, and NOAA's Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory. Much of that data is analyzed and assimilated into a computer-generated numerical prediction model. Meanwhile, land-based radar learns about hurricane wind fields, rain intensity, and storm movement. Buoys and floats collect data about ocean currents, waves, and important interactions between the sea and the atmosphere. The planes drop probes that measure a variety of features, including the ocean's salinity and temperature profile as depth increases. Aircraft fly into the storm, collecting barometric pressure and wind intensity data. Satellites collect information about the hurricane's position, wind movement, and the atmosphere's temperature and moisture levels. More data than weather modelers know what to do with, really. Hurricane forecasting begins with lots and lots of data.

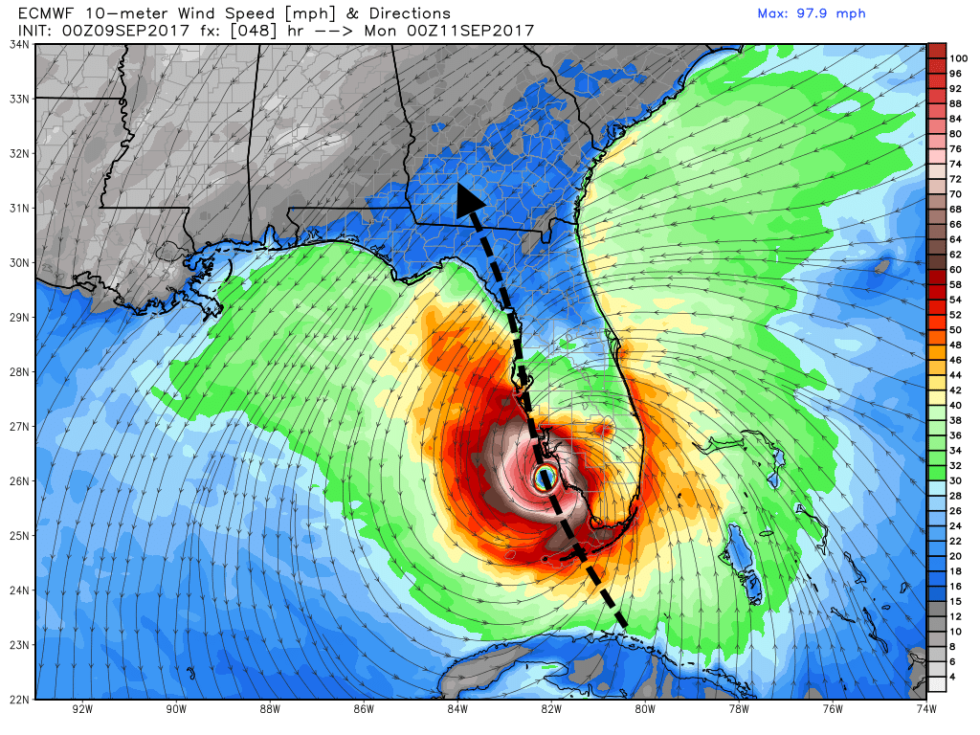

HURRICANE TRACK EUROPEAN MODEL HOW TO

"I've never seen anything that accurate that far in advance." How to Model a Hurricane "What you saw for Sandy was, I would say, the best weather forecast of a major weather system ever," says Robert Gall, who directs the Hurricane Forecast Improvement Project for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Two-day forecasts also predicted wind gusts up to 80 mph, 12 inches of rainfall, and up to 11 feet of inundation from the storm surge-predictions that almost exactly aligned with last week's storm. (For comparison, typical two-day hurricane forecasts are off by 100 miles on average.) Despite all of that, the NHC managed to predict Sandy's track to within 50 miles and two days ahead of time.

But a high pressure area over Greenland steered Sandy back toward shore, where she crashed into a cold front. Under normal circumstances, a hurricane like Sandy would have blown out to sea without giving the Northeast so much as a dirty look.

Superstorm Sandy was more complicated than a standard hurricane. By accurately predicting the track and intensity of the storm, the forecasting may have saved lives as well as millions of dollars. The storm preparations were aided by what turned out to be remarkably accurate forecasts from the National Hurricane Center (NHC), which had warned residents living in Sandy's warpath as early as five days before the storm arrived. Media Platforms Design Team As Hurricane Sandy approached New York and New Jersey last week, schools were closed, subways shut down, and low-lying coastal areas evacuated.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)